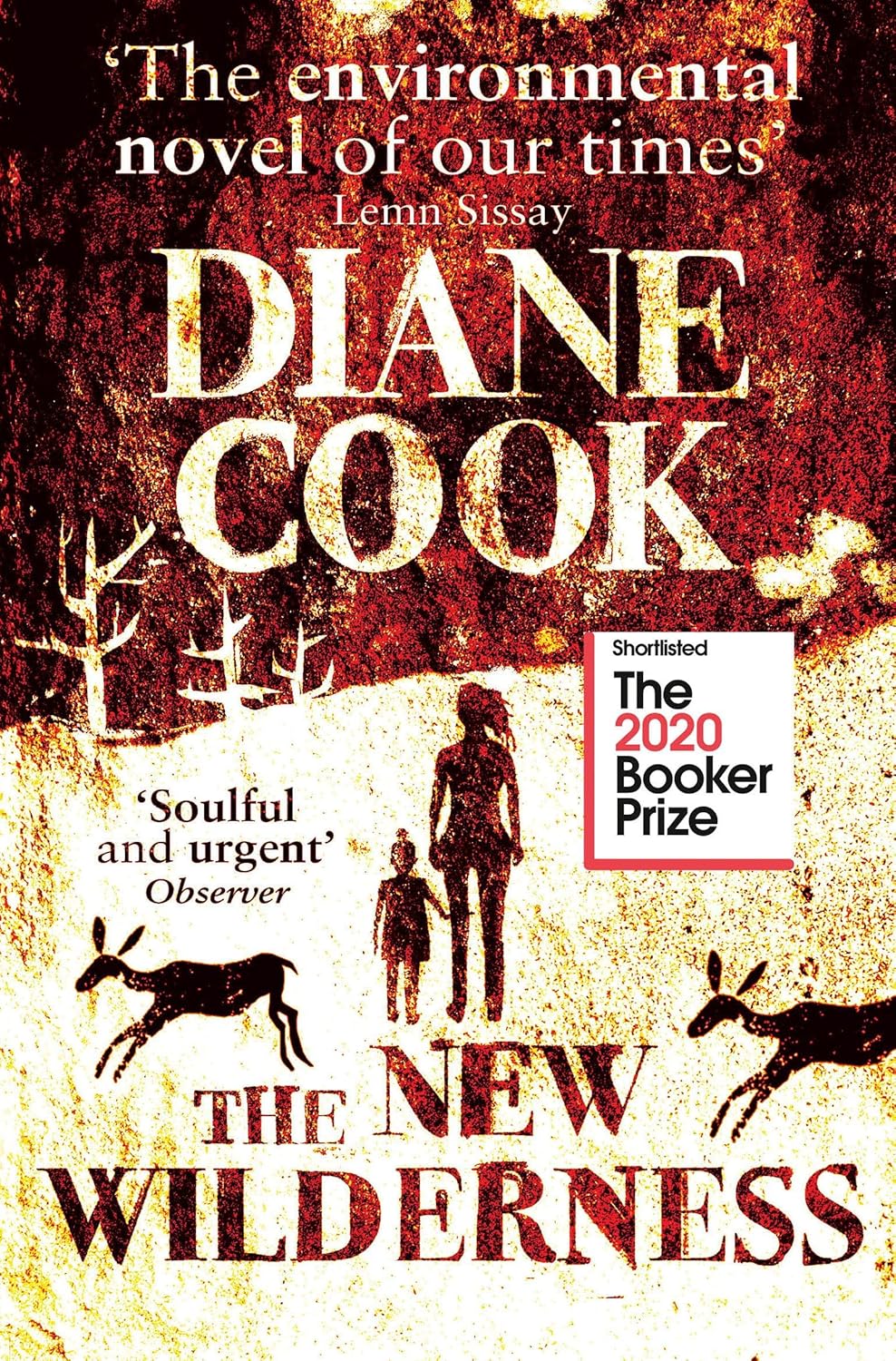

As a dyed-in-the-wool sci‑fi and dystopia lover, I went into Diane Cook’s 2020 novel The New Wilderness expecting a thought experiment about climate collapse—and got something far more intimate. Released on 11 August 2020, it’s a taut, eerie tale about a mother and daughter who enter a protected wilderness to escape a poisoned city. Or, as the German jacket copy so cleanly puts it: Eine Mutter kämpft ums Überleben in einer durch Umweltzerstörung geprägten Wildnis.

Motherhood and Survival in The New Wilderness by Diane Cook

Diane Cook frames survival not as spectacle but as routine: the stinging monotony of hunger, the ritual of moving camp, the unglamorous calculus of who carries what and why. The premise is simple and savage—leave the City’s smog-choked collapse for the so-called Wilderness State and live by rules meant to keep humans forever in motion—but the effect is complicated. Every creek crossed and ridge climbed becomes a negotiation between bodies, tempers, and loyalties.

At the book’s beating heart are a mother and daughter—Bea and Agnes—whose bond is shaped and strained by the trek. Motherhood, in Cook’s hands, is a series of small, perilous teachings: how to read sky and hoofprint, how to ration warmth and attention, how to choose the path that costs least, knowing it still costs. Agnes grows hard where Bea holds soft, and their love becomes a survival tactic with an edge—tender and tactical at once.

What lingers is how the novel refuses easy binaries. Nature is neither balm nor monster; civilization is neither comfort nor cure. The Rangers surveil like distant gods, the group behaves like a fragile pack, and the land keeps its own counsel. Cook’s sentences are clean and flinty, her scenes airy with silence and suddenly knifed with urgency. The novel keeps asking, beneath every blister and argument: what do we owe our children when the world can’t keep its promises?

A dystopian odyssey with 4 teacups

As a fan of the genre, I loved how Cook builds an odyssey from one footstep to the next. The book’s structure—episodic yet relentless—mirrors the logic of a trek: move, rest, remember, move again. There’s a shiver of myth here, but the compass is moral rather than magical: each choice tests the story’s ideas about belonging, borders, and bodies under pressure.

A brief paraphrase of a moment that epitomises the book’s pulse: on a cold morning, Bea watches Agnes outpace the group, her gait sure as an animal’s, and realises that the wilderness has become Agnes’s first language. Bea feels both pride and grief—pride that her daughter can survive, grief that survival has rewritten what “mother” means. That double exposure—strength and loss in the same glance—captures Cook’s dystopian tenderness.

Rating: 🍵🍵🍵🍵 (4/5 teacups).

I’m giving The New Wilderness four teacups for its unflinching look at maternal love under scarcity, its spare, weathered prose, and its unromantic ecological imagination. I’d normally embed the official cover here; if you’d like me to add it, share an image file or a link to the publisher’s cover and I’ll slot it in. Until then, consider this my trail-stamped recommendation: carry it into your next weekend and let it walk around in you for a while.

The New Wilderness is an elemental read—wind in the ears, stones in the shoes, a heartbeat you can count by. If you’re drawn to dystopias that measure catastrophe at human scale, this one delivers a clear, cold sip of what endurance costs and why we still pay it. Four teacups raised, hands warmed over a small fire, eyes on the horizon.