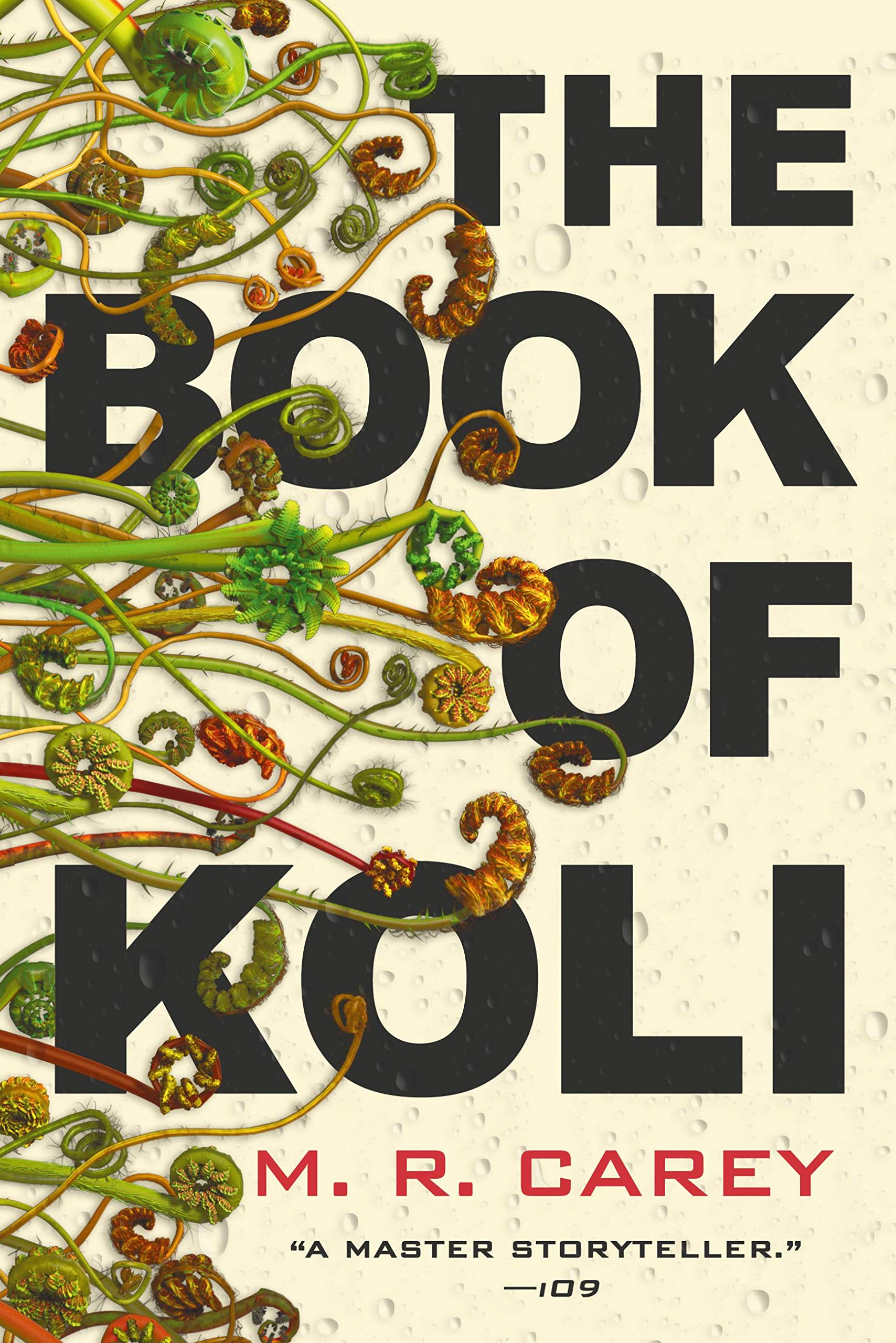

As a lifelong devotee of science fiction and dystopian tales, I couldn’t resist diving into M. R. Carey’s The Book of Koli (2020), released on 14.04.2020. It’s a striking, quietly subversive adventure set in a post-apocalyptic Britain where belief and circuitry rub shoulders and sparks fly. Short description: A post-apocalyptic world in which technology and faith collide.

The Book of Koli by M. R. Carey: faith meets tech

Carey opens on the village of Mythen Rood, where survival depends on ritual, community rules, and a fearful respect for “old-tech” relics, jealously guarded by the Ramparts. The world beyond is hostile—trees that move, seeds that kill, forests that feel like predators—and people form myths to cope with what they can’t control. Into this careful order steps Koli Woodsmith, a boy whose curiosity grows into a dangerous kind of hope.

The novel’s genius is its voice: Koli narrates in a rough-hewn, intimate dialect that feels both ancient and oddly modern, a reminder that civilisation’s seams can fray yet language will stitch new patterns. As he stumbles into the orbit of forbidden devices, the book becomes a dialogue between code and creed—between what machines can do and what people decide those machines mean. Carey shows how stories bloom wherever certainty withers.

When Koli encounters an AI companion, the boundary between the sacred and the synthetic blurs beautifully. Villagers venerate or fear tech as if it were a god; the AI, meanwhile, behaves like a lively, irreverent spirit. What results is not a simple “science versus superstition” split, but a web of dependencies in which faith shapes behaviour and tech amplifies power. Carey asks: when we can’t tell miracle from mechanism, how do we choose our ethics?

M. R. Carey’s The Book of Koli: belief and code

I love how Carey uses belief as infrastructure. The Ramparts’ authority rests on their exclusive communion with old-tech; rituals become firmware updates for a frightened community. Travellers like Ursula-from-Elsewhere embody pragmatic science—medicine, diagnostics, a sceptic’s courage—while characters such as Cup remind us that identity and agency evolve beyond any system that seeks to fix them. The clash isn’t just about who holds the gadgets; it’s about who controls the story.

I can’t provide a long quote from the novel, but here’s the gist of a favourite passage, paraphrased: Koli realises that the old world left behind more than artefacts—it left a kind of haunting; the ghosts are in the code, singing through devices we barely understand, and we choose whether to call that song magic or memory. It’s a quietly devastating moment that captures Carey’s theme: salvation might arrive sounding like a machine, but we’ll still hear it as a prayer.

As a trilogy opener, the book balances peril with tenderness, and wonder with dread. The pacing is measured, the world-building textured, and the moral questions—who deserves access, how communities police knowledge, where compassion fits in a scarcity economy—land with bite. For readers who relish thoughtful post-apocalypse with a humane heartbeat, The Book of Koli is a standout.

The Book of Koli threads faith through firmware and finds humanity blinking in the glow of old screens and new myths. It’s a lyrical, unsettling trek across a Britain where belief scaffolds survival, and technology whispers like a chorus of half-remembered gods. I’ll be carrying on with the trilogy—and recommending this opener widely. Final rating: 4.5 out of 5 teacups.